Lucy Self, Editor at Large introduces us to Artist Hilma Klint.

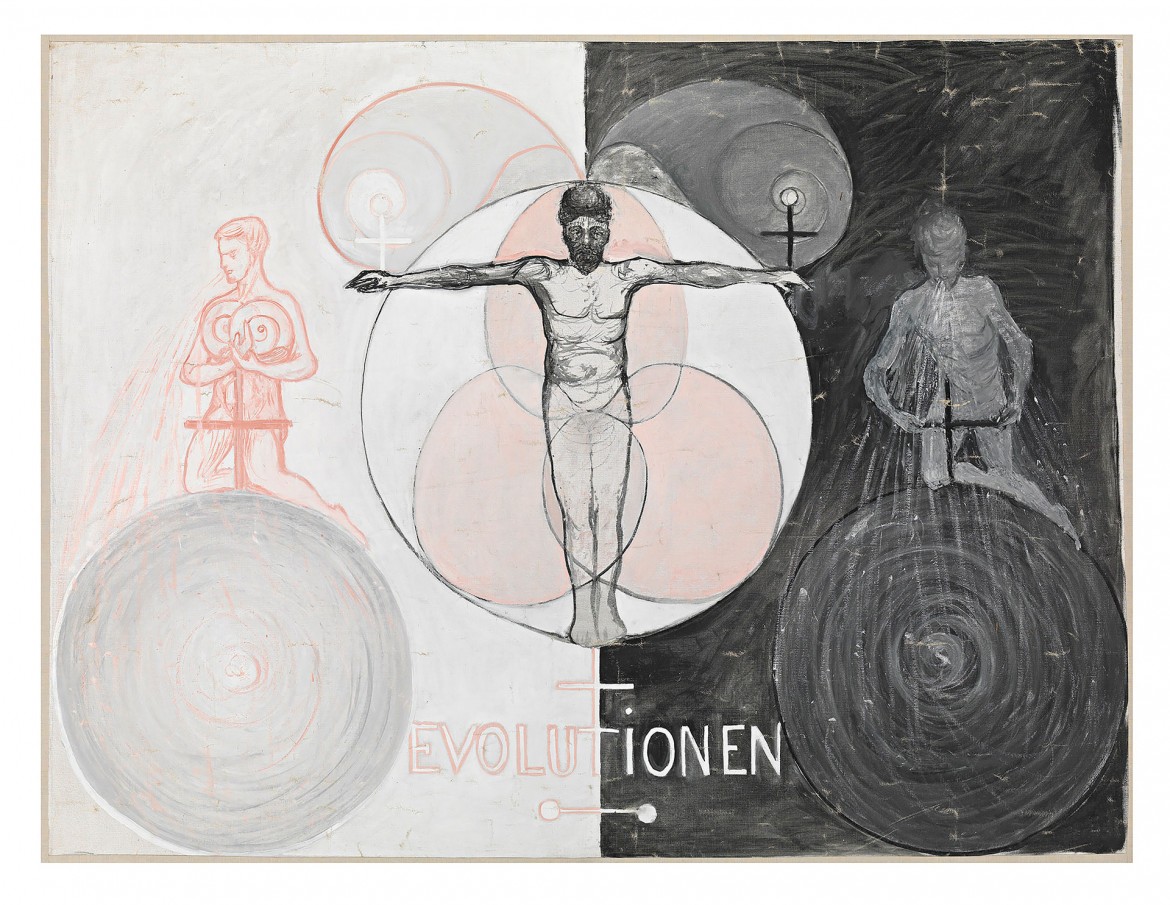

Wassily Kandinsky is generally regarded as the pioneer of abstract art. However, a Swedish woman called Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) really claims that title. Long before Kandinsky, František Kupka, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich a Swedish painter by the name of Hilma af Klint had created her first abstract painting in her Stockholm studio in 1906, five years before Kandinsky’s first abstract painting.

Who was Hilma af Klint? And how did she become an artist? Born in 1862 in Sweden, a country that permitted women to study art well before France, Germany or Italy allowed her to enrol at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1882. After graduating five years later, she took the lease on a studio in the city’s artists’ quarter and gradually gained recognition as a landscape and portrait painter.

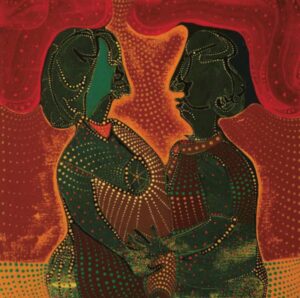

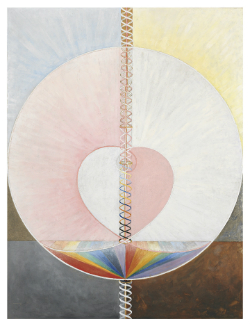

Yet it was her interest in the mystic that led Klint, then seventeen to attend her first spiritualist seance. She belonged to a group called “The Five” (a circle of women who shared her belief in the importance of trying to make contact with the so-called ‘high masters’ – often by way of séances) and her paintings, which sometimes resembled diagrams, were a visual representation of complex spiritual ideas.

In 1905 she noted that she had heard a voice that had given her the following message: ‘You are to proclaim a new philosophy of life and you yourself are to be a part of the new kingdom. Your labours will bear fruit.’

Between November 1906 and March 1907 she painted a series of abstracts, small-format canvases entitled Primordial Chaos. Some of them are reminiscent of landscapes, of a stormy sea above which flicker mysterious lights. Others break entirely free from representation, combining geometric shapes such as spirals with dynamic brushstrokes, letters of the alphabet and symbols. The mood is expressive and resembles that of the drawings she made apparently unconsciously during seances in the 1890s. The Surrealists were later to call this method ‘automatic drawing’.

What led Klint to abstraction? An interest in invisible forces was widely accepted, rather than being limited to followers of the occult. By the end of the nineteenth century, the natural sciences had already discovered many invisible forces, including infrared light, X-rays and electromagnetic fields. These phenomena presented the arts as well as science with new questions: the question was could natural forces, the unseen feelings be captured and presented?

The importance that abstraction would assume in the history of art becomes clear only at a later date. Abstract painting is abstract. It confronts you. It challenges you and ultimately it leaves you questioning how you feel about it. So often we are dulled by needing to understand the relevance, the pictorial story; abstract art exists in its right to remain fluid and indefinable. Ironically herein lies the problem: we are not told what to think. The endless conundrum lies in the fact that we all know that abstract art can be art but we don’t know if whether to admire it or even start to understand it!

Quintessentially this is the fundamental question that life poses us: do we understand or even like it?